- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Ellen Tani’s Second Sight: The Paradox of Vision in Contemporary Art at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art was a striking exhibition that brought together a diverse array of artworks engaging issues of visibility and invisibility in poetic and literal ways. Works by Robert Morris, Bill Anastasi, Richard Serra, Félix González-Torres, Glenn Ligon, Lorna Simpson, Nyeema Morgan, and Shaun Leonardo (to name just some of the contemporary artists of various generations in the show) “problematiz[e] the deeply interwoven history of vision . . . knowledge,” and power (1). Tani showed new aspects of these creators’ oeuvres, foregrounding the tactile and sonic features of familiar works. The “ocularcentrism” of the art gallery, one of the possible paradoxes that the title refers to, was not just contested by the artworks, audio descriptions of some of the projects enabled visitors to digest the contents nonvisually (71–81). A handsome catalogue with numerous color images and essays by Tani and Amanda Cachia accompanied the exhibition.

Second Sight, an apt title, hails from W. E. B. DuBois’s The Souls of Black Folks (1903). Indeed, Tani ambitiously wove together the legacies of DuBois and Marcel Duchamp: specifically, the latter’s critique of “retinal art” (works appealing to eyesight alone, rather than the intellect) that was so important for the development of conceptual art, which melded with the former’s “double consciousness” (“a second-sight” that “lets him [the negro] to see himself through the revelation of the other world”) (DuBois in Tani, 5). The show was not limited to this dual heritage. Doublings and redoublings recurred throughout the galleries.

From the outset, visitors had to employ senses beyond sight to confront issues of race in America. Steve Reich’s Come Out (1966) sounded in the vestibule adjoining the lobby and galleries. Reich’s breakthrough, minimalist composition consists of two-channel multiplications of the words “come out to show them,” which move in and out of sync. The wall text explained that the phrase was split from the testimony of Daniel Hamm—one of the Harlem Six, a group of teenagers falsely accused of a 1964 murder. In order to receive medical treatment following repeated beatings while jailed, Hamm needed to provide his captors with visual proof of injury (in the form of external hemorrhaging): “I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.” Thus, when historicized, the fragment broadcast the history of injustice and police brutality upon black bodies; it evoked traumatic repetition and conjured the absent context from which Reich sampled the audio. Upon entering the galleries proper, visitors encountered a second Come Out (2014), that by Ligon. A collision of conceptualism and history painting, his spare, large-scale canvas translates and materializes the multiplied phrase in black paint. Layers of silk-screened sans serif texts, vacillating between legibility and incomprehensibility, yield vertical bands of light gray and ash that formally recall the geometries of color-field painting. The artist gives Hamm’s words a further afterlife, signaling the resonances of past struggles in the era of Black Lives Matter.

Ligon’s reprisal of Reich is just one of various dialogic dyads. Tani staged provocative pairings such that works came into focus as second “sites”: they work through or extend concepts begun by others, providing gallerygoers with additional vantages. For example, language and materiality concerned Robert Barry in his taciturn Untitled (Had To) (n.d.): a single crimson canvas with text that seems to float on its surface; the red painting hung close to Adam Pendelton’s Refusal of Work (2006), a screenprint reproducing the front cover of Barry’s Art & Project Bulletin #17 (the interior announced that “during the exhibition the gallery will be closed”) on a mirror-finish steel plate in which the reflected surrounds overpower the text. Lorna Simpson’s Cloudscape (2004), a stark, haunting video “portrait” of Terry Adkins, provided a view of the artist whose contemporaneous kinetic sculpture Off Minor (from Black Beethoven) (2004), a monstrous music box, appeared in Second Sight’s first room. Simpson’s series of close-cropped closed lips, 7 Mouths (1993), rhymes with Anne Hamilton’s Face to Face (2001), photos created from a pinhole camera placed inside Hamilton’s mouth. Sophie Calle’s The Blind and Blind #14 (both 1986) and Joseph Grigley’s missive reactions to Calle’s exhibition Les Aveugles, Postcards to Sophie Calle (1991) cohabitated.

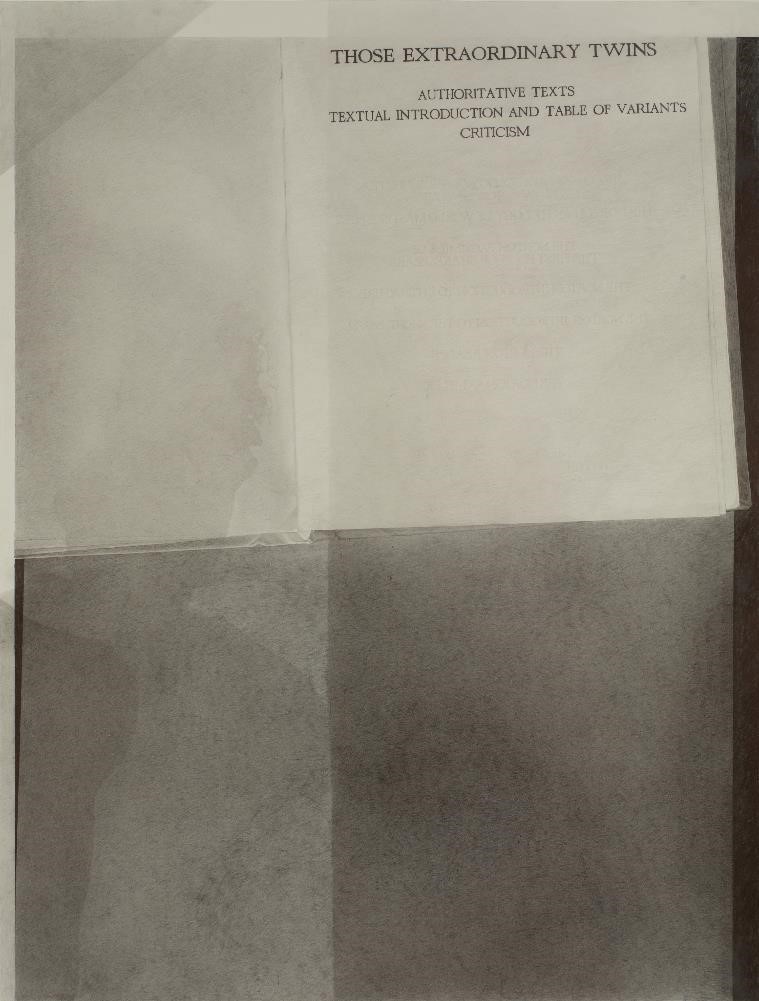

Myriad doublings come in Nyeema Morgan’s Like It Is: Those Extraordinary Twins (2016). Morgan meticulously rendered a scanned or photocopied image of the cover page of a 2005 edition of Mark Twain’s The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins (1894) for this complex artwork. In her graphite drawing, the codex forms a trapezoid of white and light grays above the far darker void of the flatbed. Twain’s double text is cropped so that only the title of the less famous story, Those Extraordinary Twins, appears within the frame. The conspicuous absence implies that the drawing is haunted by a presence of the other story. According to his introduction, Twain had initially intended to develop a single narrative around two disabled characters, a pair of Italian conjoined twins (the titular figures). Nonetheless, another pair of men born nearly simultaneously—and switched—became “inordinately prominent and . . . persisted in remaining” in the tale: a slave and the child of the master exchange positions. Questions of the arbitrariness of race and the legacy of slavery bubbled up and overpowered the plot. A drawn double silhouette cast over the left of the folio, apparently the outlines of Morgan at work, brings the studio labor that produced a singular handmade original from a digital copy to the site of display as well.

Many other tour de force drawings appeared in the exhibition. Shaun Leonardo’s paired charcoals, based on the iconic image of Mohammed Ali’s knockout of Sonny Liston, respectively depict a prostrate Liston and a crowd of viewers and reporters with a ghostly trace of the boxer. While mined from the margins of a spectacular source, Leonardo’s drawings also owe something to William Kentridge’s combination of drawing and cinema in projects like Felix in Exile (1994). Equally, Leonardo channels the work of George Bellows, who centered on boxers, fans, and race in his Both Members of This Club (1909). Leonardo investigates the apparent paradox of societal hypervigilance and (mediatic) hypervisibility of black bodies that can occur simultaneously with invisibility (as described by Ralph Ellison) and lack of representation. Tony Lewis’s Domain (2015), a massive rendering of a stenographer’s mark in graphite, points to language’s concrete and abstract qualities. Lewis additionally produced two works in situ, wall drawings composed from graphite-dusted rubber bands stretched over screws.

Six drawings by Bill Anastasi (in addition to two sound objects, a cast-iron radiator and a pulley, shown at the Virginia Dwan Gallery in 1966), including some “blind drawings” for which he relinquished control and let environmental factors determine his mark making, demonstrated his range. Tani implicitly moved to revive his reputation as a key art historical figure, placing his work alongside projects by his contemporaries, including Morris, Serra, and Barry. Indeed, her curatorial selection seemed to confirm (and even expand) James Meyer’s “return of the sixties”: the exhibition clearly proved the continued relevance of the culture and artistic strategies of that decade for the contemporary (post-1989) moment. Second Sight proposed a further revision of the history of contemporary art, as its cast of fairly canonical artists performed an interrogation of “visual art.” I was fortunate enough to visit Second Sight on the day that Carmen Papalia facilitated a Blind Field Shuttle Walk on Bowdoin’s quad. Papalia has developed the notion of the “non-visual learner” to describe ways of engaging with new information without vision. His humbling participatory project prompted visitors to reorient themselves in the world and hence, extended Second Sight’s mission beyond art and into life.

John A. Tyson

Assistant Professor, Art Department, University of Massachusetts Boston