- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

(Click here to view the exhibition website and related content.)

The basis of the exhibition Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) is just a blip in history: six weeks. That is the amount of time that the show’s central figure, Prussian naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), spent in the United States in 1804. But curator Eleanor Jones Harvey wants us to realize that this brief stay planted a seed of influence that was “immediate, sustained, and profound” (26). On the tail end of an extensive, multiyear expedition to South America, the young Humboldt visited Philadelphia and Washington, DC, enchanting and motivating the new nation’s prominent thinkers. The infatuation was mutual, for Humboldt (who apparently called himself “half an American”) would stay active in US science and politics until the end of his long life. He had his hand in endeavors from the laying of the transatlantic cable to the founding of the Smithsonian itself.

Harvey’s exhibition is intellectually timely in that it brings Humboldt (hardly a household name in the United States) back into visibility at a moment when his ideas are enjoying something of a renaissance. Humboldt’s core belief was that all living things were linked in what he called a “unity of nature,” a concept not unlike the present-day ecological understanding of the earth. Circa 1800, though, Humboldt’s revolutionary theory—developed from a synthesis of philosophical reasoning and empirical observations collected from around the globe—challenged the prevailing human-centered hierarchical ordering of nature. Later in the nineteenth century, as specialization and technological advancement began to define the sciences, Humboldt’s wide-angle perspective and globetrotting observations began to look like those of a romantic amateur rather than a serious scientist. The ecological crisis today, however, demands that we think again in Humboldt’s terms—about our modest place in a natural world that is globally interconnected.

Practically, though, the show’s timing could not have been worse. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, SAAM has only opened to the public for a few short weeks. Most museumgoers (myself included) have not been able to experience Harvey’s installation in its multidisciplinary breadth. The show’s theatrical centerpiece, for one, is not an artwork at all, but a mastodon skeleton. The massive prehistoric creature—the largest land animal then known when its bones began surfacing in late eighteenth-century America—had helped to forge a long-lasting bond between Humboldt and his American associates. Just before Humboldt’s visit, the first complete mastodon skeleton made its debut at Charles Willson Peale’s Philadelphia Museum. There, the Prussian explorer laid eyes on the creature he had read about as the “American incognitum” in Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). In Jefferson’s writings, the creature was more than a curiosity: it was his best evidence of the superiority of American nature in the face of European theories of colonial degeneracy in the New World. The mastodon on view at SAAM, on loan from Darmstadt, Germany, is the very creature that once stood in Peale’s museum. Now, for the first time in nearly two centuries, it is accompanied by two of Peale’s most celebrated paintings documenting its excavation and original installation, The Exhumation of the Mastodon (ca. 1806–8) and Artist in His Museum (1822).

Spectacular then as it is now, the mastodon serves as the Smithsonian exhibition’s symbolic as well as physical center—almost a kind of proxy for Humboldt himself, a man of once mammoth presence. Arrayed around the immense skeleton are thematic galleries that showcase Humboldt’s web of connections to American artists, ideas, and places.

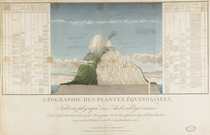

Nearly a year into the pandemic, it has become obvious that museums have a great deal to lose in the shift to virtual experiences taking place in the interest of public health. A loss of material presence is palpable in any virtual exhibition, and in the Humboldt show, it is not limited to the bones of a prehistoric giant. So much of nineteenth-century experience was oriented to details, like those found in profusion in the hand-colored print Géographie des plantes Équinoxiales (1805), a complex infographic meets topographical map of the Andean ecosystem that Humboldt called his Naturgemälde (“picture of nature”), and Frederic Church’s blockbuster landscape paintings, which beholders once inspected at close range with their opera glasses. Technology might allow us to zoom into these artifacts on screens, but we lose the sense of scale that accompanies in-person encounters—a crucial awareness that can generate the awe that period viewers probably felt before these same objects.

Fortunately, the exhibition’s virtual presence has been propped up by a suite of well-crafted and accessible video tours, recorded lectures, and even animated features. In the absence of live programming, these are pedagogical resources with much greater longevity than a ticketed tour. For better or worse, though, they have the cumulated effect of shifting the show toward the biographical. Whereas Humboldt’s place in the galleries is more often implied than literal, as the originator of ideas informing the creators and collectors of the exhibition’s hundred-plus objects, he is front and center in the virtual offerings. Given the brevity of internet-friendly audiovisual content, Humboldt—a colorful, ambitious, and original figure of the past—quite literally steals the show. Artworks that might have grasped our attention on the gallery floor become mere decor hung on a man who was larger than life.

The website also includes image reproductions of roughly half the exhibition’s total object list, each accompanied by short texts that map out links between Humboldt and the artwork’s maker, sitter, or collector. The downside of this linear ordering is that the exhibition’s leitmotif of the web or network, which could have been made tangible through visual connections between objects in a physical gallery, easily gets lost.

The show’s exhaustive and deeply researched four-hundred-plus-page catalog is a veritable who’s who of the Euro-American scientific, artistic, political, and intellectual world of the nineteenth century. Harvey, the book’s author, precisely teases out the timelines of travel itineraries, chance meetings, and correspondences—sometimes down to the day—of these varied thinkers and creators. Scholars of American art will immediately recognize Harvey’s canonical cast of characters (Thomas Cole, George Catlin, Albert Bierstadt, and Samuel Morse, among others), though few would have been able to pinpoint their link to Humboldt before reading Harvey’s work. The book makes obvious that Humboldt’s personality and writings permeated all aspects of American culture. His pursuits were so diverse and his networks so extensive that, as Harvey tells it, we are “never more than two degrees of separation” from Humboldt himself; we need only to “dust for his fingerprints” (33, 35).

Harvey’s impassioned forensic investigation has also yielded some bold claims about the history of American art. Humboldt, she argues, is at the root of national, cultural projects like landscape painting, which many Americanists would consider endemic. Harvey proposes that it was Humboldt who “emboldened” Americans to “identify unique features of [their] landscape and claim them as emblematic of the country’s identity” (152). Her strongest evidence is in the work of Frederic Church, the most famous nineteenth-century practitioner of the genre. A devoted acolyte, Church took pains to trace Humboldt’s footsteps in the Andes and later made paintings that sought to embody Humboldt’s concept of the unity of nature. But Harvey does not stop at Church. She seemingly credits this singular European influencer for the acceptance and flourishing of a “wilderness aesthetic” in all of nineteenth-century American literature, writing, and art (156).

Perhaps the most notable shortcoming of Harvey’s otherwise skillfully conceptualized and executed project is its tendency toward hero worship. In the catalog and interviews, Harvey paints Humboldt as a man of almost superhuman strength and intellect (he published thirty-six books, knew nearly a dozen languages, held a mountaineering record for several decades, slept only four hours a night, and managed to charm the ladies to boot). It is easy for us to become just as infatuated with the foreign polymath as early Americans were in 1804. Harvey also stresses Humboldt’s humanitarianism—his admiration for democracy over monarchy, his support of abolition on moral grounds, and his advocacy for women and Indigenous people in his research endeavors.

Accordingly, the rich web of connections that Harvey weaves around her protagonist tends to favor positive and progressive narratives. In chapter 2, for instance, we learn that Humboldt’s support of expeditions to the American West and the landscape art they generated fostered land appreciation and a conservation mindset that eventually led to the establishment of national parks and monuments. Yet, there are also darker legacies of these expeditions and their accompanying imagery that get brushed aside: territorial conquest, violence toward Indigenous groups, and resource depletion. Even in a later chapter, “Humboldt and Native American Ethnography,” where Harvey acknowledges that explorers in Humboldt’s circle (Catlin, Prince Maximilian, and Karl Bodmer) disrespected and exploited Indigenous peoples, she couches these transgressions in Humboldt’s admirable desire for ethnographic knowledge.

Humboldt came from a world of white, aristocratic, and imperialist privilege that shaped his interactions not just with Americans (then citizens of a peripheral nation and recent colony) but also with his Indigenous informants and large crew of assistants. Humboldt’s democratic ideals and his proto-ecological worldview were no doubt ahead of his time. But if we too readily recast him as a modern hero—a humanitarian and environmentalist suitable for today’s progressive politics—we also overwrite a more difficult, but no less important, history of the unsavory prejudices and violent legacies that came with his privileged position.

Maggie M. Cao

David G. Frey Associate Professor